September 15, 2020 Father De Celles Homily

24th Sunday in Ordinary Time

September 13, 2020

Homily by Fr. John De Celles

St. Raymond of Peñafort Catholic Church

Springfield, VA

One of the most difficult sins to confess to a priest,

and yet probably one of the most common,

is the sin of being unforgiving.

I don’t know how many times people have come to me in confession

and expressed tremendous sorrow and confusion

over their inability to forgive someone.

And yet forgiving is essential to the Christian life.

As today’s Gospel reminds us, when Peter asks Jesus:

“Lord, if my brother sins against me,

how often must I forgive?”

And Jesus tells him: “seventy-seven times.”

In the Scriptures, the number seven symbolizes perfection,

so that the number seventy-seven

stands for an infinite number—“always” or “every time”.

Jesus’ instruction here is one of the hardest for most of us to understand.

To think that we must forgive every single offense against us,

and anyone who does it.

It seems impossible, but Christ makes it a condition of God forgiving us, saying:

“his master handed him over to the torturers…

So will my heavenly Father do to you,

unless each of you forgives your brother.”

Some offenses seem just too big to forgive:

this week many of us can’t help but think about

the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001.

Or we struggle forgiving folks whose politics seems to us

to be completely un-American,

or who bring rioting and violence to our cities.

But we can also think of much more common offenses which are also terrible,

things like rape or child abuse, or adultery.

And it isn’t just these heinous crimes that are hard to forgive

—sometimes the offenses hardest to forgive are the smallest:

how many of us still hold on to the petty slights from years ago?

You still cling to the pain of your father missing your big game,

or your sister always being the “favorite,”

or your spouse forgetting an anniversary.

Sometimes it’s not just one offense but a whole series,

or even a lifetime of offenses.

For example, the wife whose husband has been verbally abusive

throughout 30 years of marriage.

Or the bigot, who lynches no one,

but makes his point with a lifetime of petty prejudices.

How do we forgive these wounds that weigh so deeply on our hearts?

Well, the first thing we need to do

is make sure we know what we mean by “forgiveness.”

Unfortunately, some people think that “forgiving” means “forgetting”,

and that we have to stop feeling the pain people caused us.

But as the Catechism (2843) reminds us:

“It is not in our power not to feel or to forget an offense.”

It’s not necessary to pretend that a person hasn’t hurt us

in order to say we’ve forgiven them.

Sometimes it would even be irresponsible to do so

—if a stranger hurts your child, you should forgive

but you should not forget, so you can protect your child in the future.

The same thing applies with 9/11 and terrorists:

we must forgive, but we should never forget.

Not even God forgets the sins He forgives

—if He did, how could He give us the grace to avoid them in the future?

Look at the king in Jesus’ parable today:

at first he forgives the debt, but he doesn’t forget about it,

or else how could he later get angry and reinstate that same debt.

Then what is necessary for forgiveness?

Fundamentally, only this is necessary: love.

Regardless of whether the offense against us is terrible or petty,

the reason most of us can’t forgive is because

instead of loving the one who hurts us

we cling to the anger and the hate they provoked.

But as the prophet Sirach reminds us in today’s first reading:

“Wrath and anger are hateful things,yet the sinner hugs them tight.”

What a great line: the sinner “hugs” “wrath and anger” “tight”.

And he admonishes us: “set enmity aside…and hate not your neighbor.”

Again: we have to make sure we know what “anger” means in this case.

The Catechism reminds us that “anger” includes “a desire for revenge.”

But it also reminds us that that’s not always a bad thing.

When we desire vengeance in order to do evil to someone—that’s sin.

But when we desire vengeance to impose restitution

or to “to correct vices and maintain justice,”

that’s a righteous and noble thing.

Like the King in today’s parable, Jesus tells us:

“Then in anger his master handed him over to the torturers

until he should pay back the whole debt.”

Anger is what Catholic theology calls a “passion”—an emotion.

Like all passions it can be warped to move us to do evil things,

or it can be harnessed to motivate us to great things.

So, for example, after 9/11, anger motivated many young Americans

to sign up to defend their country in the armed forces: to become heroes.

It also motivated Martin Luther King Jr. to peacefully, but forcefully,

speak out for the rights of Black Americans.

But that anger can also be easily twisted into unjust anger:

whether it’s hatred for all minorities, like Blacks or Muslims,

or Black Lives Matter rioting and attacking police.

Just anger is consistent with love

—but unjust anger, the “anger” Sirach is talking about,

is infected with hate.

And it’s this unjust or hateful anger that we cling to when we can’t forgive.

How do we let it go?

The thing is, God looks at us and sees the very same offenses against him

that others have committed against us.

He sees our big and exceptional crimes.

He sees our petty slights.

And he sees a lifetime of sins, large and small, in every one of us.

But He forgives us because He loves us.

And He calls us to love in the same way.

But how do you love someone who’s hurt you?

Today’s parable tells us how.

Now, the parable presents sinners as owing something to God.

What do we owe him?

Actually, since he gave us everything we have free of charge,

we owe him everything.

But if you think about it,

everything God gives us is simply an expression of His gift of love.

And so what we really owe him is that same thing: love.

Now Jesus makes it clear that when Scripture talks about “love”

it’s not talking about a warm and fuzzy feeling.

Love is not the same as “liking” someone,

or being attracted to their personality, or enjoying their company.

Love is a profound desire for the good of the other person.

But how do we know how to love God?

He tells us over and over again:

“If you love Me,” Jesus says, “you will keep My commandments.”

If you love Me you won’t take My name in vain,

and you’ll recognize that I’m the only true God.

If you love Me you won’t abuse the people I love and that I give to you to love,

like your parents, or your spouse;

you won’t hurt, steal, lie to or abuse, much less kill, your neighbor

—because I love them and so should you.

So every time we break the commandments, in large ways or small,

every time we sin, we are failing to love God.

We are failing to pay back to Him the love that we owe Him.

Now, the parable also tells us:

“the servant fell down, did [the king] homage, and said,

‘Be patient with me, and I will pay you back in full.’

And the king is so moved,

that he realizes he already has more than enough money

and literally forgives the debt, wiping it off the books.

God is like that rich king, so that when we go to Him,

and beg Him to give us another chance,

promising to try our best to love Him,

to start making payments on the debt,

He loves us so much that

like the king who has more money than he could ever spend,

God simply forgives the great debt of love we owe Him from the

past,

and looks forward to receiving the love we promised from now on.

Still, how does this help us to forgive our “debtors”

—to love those who don’t show us the love they owe us?

Jesus tells us in Scripture:

“With men it is impossible, but not with God;

for all things are possible with God”.

The thing is, God’s love is so generous

that He not only forgives our debt to Him,

but He also gives us even more of His love:

enough for us to share with others,

and enough so we won’t need to worry about

what they owed us from the past.

He fills us with His love, and with His love, we can forgive others.

What is necessary is love—the love of Christ.

So that every time we go to confession and every time we receive Holy Communion, we receive an outpouring of that grace—that love.

In confession that love washes away all our sins, mortal and venial,

and in Holy Communion it takes away venial sins.

That’s the power of Jesus’ love.

We know that the Mass is a representation of Christ’s sacrifice of the cross.

And on the cross Jesus looks down on the soldiers who nailed Him to the cross,

the Pharisees and Sadducees who falsely accused Him.

He’s dying for their sins, paying back the debt of love they owe to the Father,

but what does He say?

“Father, forgive them.”

Words of forgiveness, words of love.

And that same love, from the Cross, pours into us

in the Eucharist and Confession and fills us with so much Divine love,

that we can love as Jesus does, even those who have offended us.

___

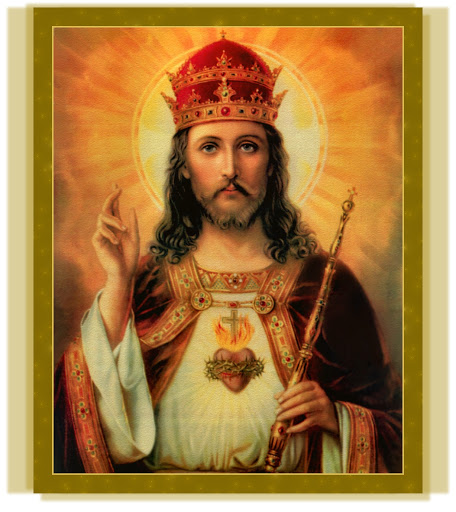

Today, as we enter into the mystery of the Holy Mass,

let’s imitate the servant

by falling down in worship before our king begging forgiveness of our debt,

and promising to give Him all the love He is due from this day forward.

And let us ask the Lord to give us the grace today

to love those who have hurt us,

to forgive those who have trespassed against us.

Let’s not be distracted or discouraged by false notions of forgiveness,

by memories that will not fade, or anger that is just.

But rather, let us open our hearts to the power of the love of Christ,

as He comes to us in the Most Blessed Sacrament of His Infinite Love,

the Eucharist.

And let us leave here today with that love,

the power to forgive our brother

“not seven times, but seventy-seven times.”